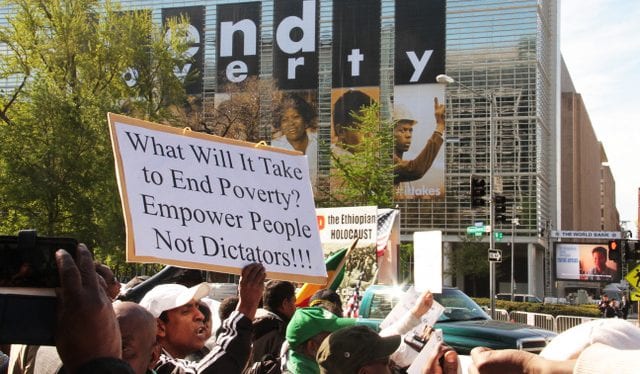

The World Bank is having an existential crisis.

For decades, the bank was the premier development finance institution, doling out loans to developing countries without rival.

The World Bank was also a pioneer – though not always willingly – in creating standards to protect people who could be harmed by its investments. In 1980, it became the first development agency to create a resettlement policy, which aims to ensure that communities displaced by bank-funded projects are not left worse off.

Adopting these protections was incredibly important for an institution that has historically funded large infrastructure projects that have displaced millions of people. Indeed, the policy was adopted in response to violent forced evictions carried out to clear the way for a World Bank-funded dam in Brazil. The scandal embarrassed then President Robert McNamara and exposed the inherent contradiction of impoverishing entire communities in the name of fighting poverty.

Yet now, with the recent rise of development financiers in China and Brazil, the World Bank is losing influence – and confidence in its commitment to protect communities negatively affected by its projects. New competitors are hungry for business and are offering loans with fewer strings attached.

As a result, the World Bank finds itself at a crossroads unparalleled in its 71-year existence. Does it double down on its commitment to responsible development in a bid to distinguish itself from an increasingly crowded field? Or does it abandon those principles in order to make its loans more attractive to the autocratic governments it frequently does business with?

Sadly for those who care about human rights, the bank is doing the latter – abandoning its principles – while paying lip service to strengthening them. Without pressure from donor countries, including the United States, essential protections that have been in place for over 30 years will be gutted.

In 2012, the World Bank began a review of it social and environmental safeguards, a process that is nearing completion. At the beginning of the review, bank officials said all of the right things. The bank had “no intention of diluting the safeguards,”President Jim Yong Kim told civil society groups at a town hall event.

The reality has been much different. In August of last year, the bank released the latest draft of its proposed new standards. In important respects, they are much weaker than the current policies.

The new standards move away from a rules-based system, rooted in a commitment to doing no harm, to a more aspirational and flexible set of standards. The draft rules give the bank’s loan officers significant leeway in negotiating with borrowers if, how and when the poor – and let’s be clear, it is never the well-to-do who are forced to move for development – should be protected.

The new system also shifts much of the responsibility for managing the impacts of projects from the World Bank to borrowers. In essence, the bank will be able to take a borrower’s word on whether a project is meeting its standards. This is inviting abuse, given the bank’s track record of lending to some of the most repressive governments in the world.

Why do these changes matter? Despite its diminishing influence, the World Bank remains a powerful player in development finance. Other institutions, including the new BRICS-backed New Development Bank and the China-led Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, are closely watching the safeguards review process. If the World Bank adopts weakened standards, it could trigger a race to the bottom.

Another reason is that President Kim wants the bank to get back into the business of financing “transformational” mega-projects, such as large hydropower dams, something it had moved away from in recent years.

The bank is doing this despite decades of research showing the profound harms of mega-dams. Not only do they displace people in their immediate vicinities, they create changes to river ecosystems that can destroy the livelihoods of many more people living downstream.

One such mega-dam is Nam Theun 2 in Laos. The World Bank-financed project displaced as many as 155,000 people, according to a panel of experts who monitored the project. According to new research, due to a failure of the bank and Lao government to properly implement the safeguards, the majority of people impacted have been left worse off. And for what? Since the dam became operational in 2010, almost all of the power has been exported to Thailand, despite one in four Laotians not having access to electricity.

With the World Bank now eager to fund dozens of similar dam projects around the world, a stronger system of human rights and environmental protections is needed now more than ever. Yet the draft safeguards, as they currently stand, fall well short of that task. If approved by the bank’s board in the coming months, they will open the door to many more catastrophes like Nam Theun 2.

The World Bank’s donors must act now to prevent that from happening. Every three years, the bank asks for contributions from wealthy nations to provide low-interest loans to the poorest countries. Congress is currently considering that request.

The United States should use its considerable leverage as the bank’s largest shareholder to demand that it adopts strong, mandatory safeguards for its projects. Congress must insist that U.S. taxpayer money is used to fight global poverty, not create it.

Read original on Huffington Post.