Asset managers advertise ESG investment funds as a way for everyday investors to align their money with their values. The rising popularity is fueled by industry executives and marketing materials that claim they are helping investors “build better portfolios for a better world.”

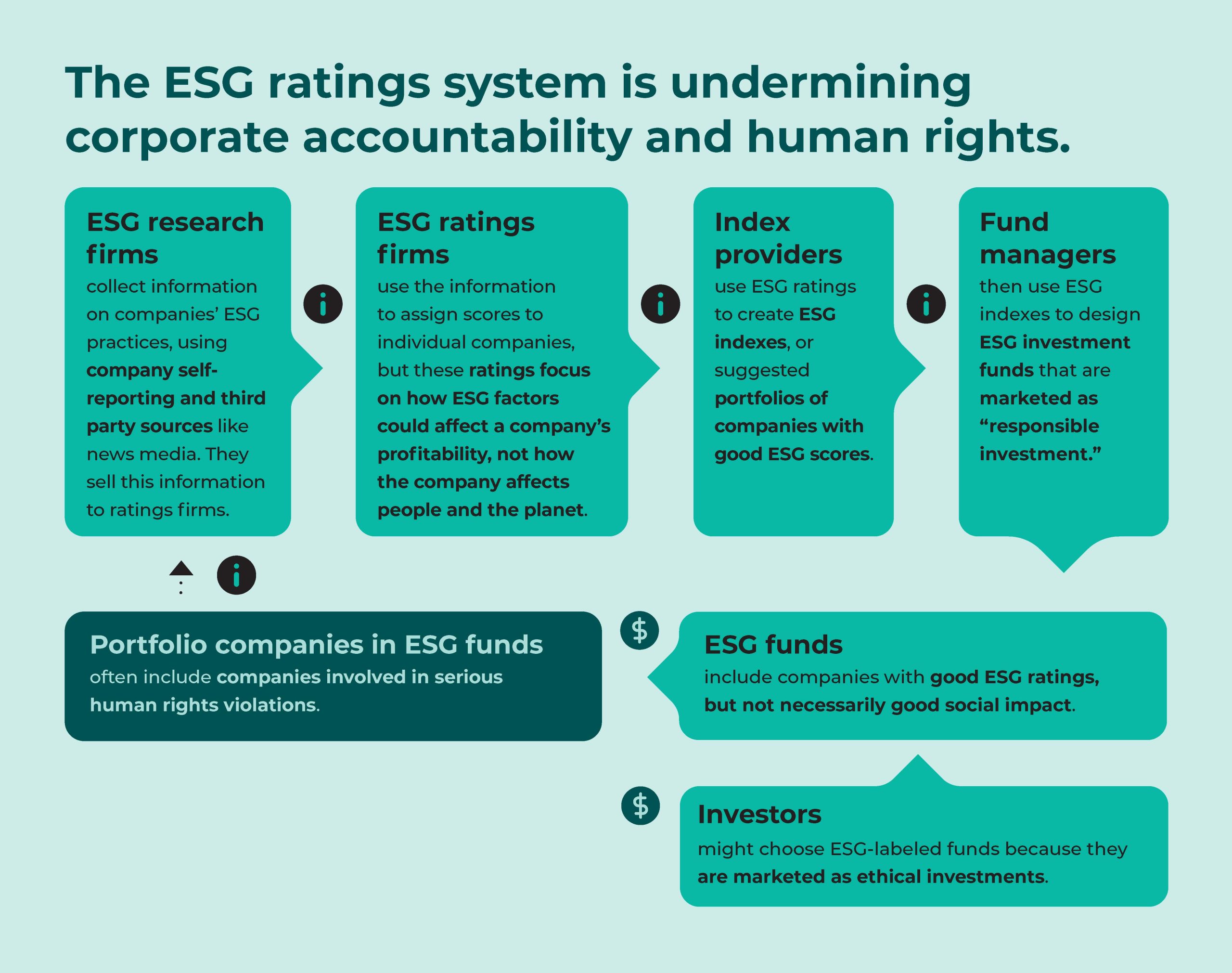

But companies’ ESG ratings—which are used to tailor investment portfolios and determine which companies benefit from ESG investment—only reflect information that rating agencies consider “financially material.” Contrary to what the average investor would expect, ESG ratings often disregard evidence of a company’s negative impact on communities, workers and the environment—even gross human rights violations.

Even when such evidence is considered, ESG ratings can mask human rights abuses and other destructive corporate behaviors because they combine a wide range of environmental, social and governance indicators into a single score. That means a company can offset bad behavior in one area—e.g., land grabbing or use of forced labor—with unrelated initiatives in another—e.g., launching a new recycling program or improving the diversity of its board. Often, the end-result is greenwashing.

ESG index providers are firms that translate ESG ratings into ESG indexes—or lists of companies they consider to have rated highly on ESG factors—which greenlights those companies for inclusion in ESG-labeled investment funds (i.e., funds with names that include phrases like “ESG Leaders” and “ESG Screened”). The leading index providers—MSCI, FTSE Russell and S&P Dow Jones Indices—have become the gatekeepers of trillions of dollars in capital, giving them enormous leverage with companies seeking a spot on their indexes—leverage they can use to ensure that the companies they are promoting as “responsible investments” are not involved in human rights abuses. In fact, they have a responsibility to exercise that leverage under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, but they almost never do.

The low bar for securing a place in ESG funds does more than direct “responsible investment” to the wrong place. It makes it harder to hold some of worst corporate offenders accountable. The “ESG” stamp of approval undermines the efforts of communities and human rights defenders to secure redress for corporate abuses by making investors less likely to engage and use their leverage to compel action. We know this from first-hand experience in our casework.

In February 2024, Inclusive Development International filed complaints against MSCI, FTSE Russell, and S&P Dow Jones Indices for violating OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct. As the complaints explain, the firms did so by promoting ESG-labeled investment in companies linked to Myanmar’s military, despite its history of abuses, including the Rohingya genocide and ongoing violent crackdown on pro-democracy activists. The complaints, filed jointly with our partners ALTSEAN-Burma and Blood Money Campaign of Myanmar, were submitted to the U.S., U.K., and Dutch National Contact Points for Responsible Business Conduct (NCPs), which are government offices tasked with handling complaints alleging noncompliance with the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises.

Read the complaints here.

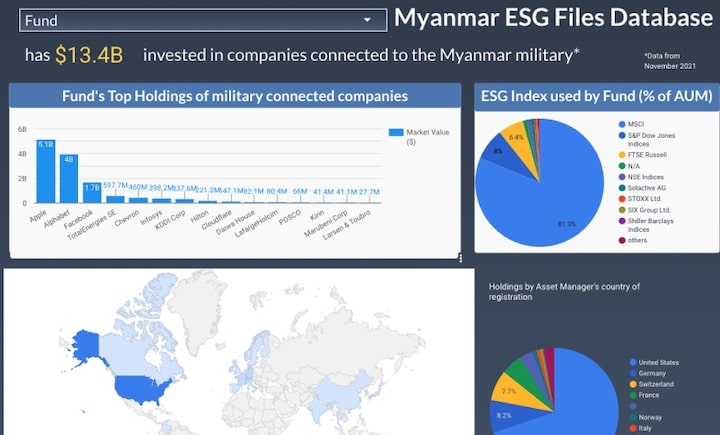

The complaints are based on extensive research revealing that MSCI, FTSE Russell, and S&P Dow Jones Indices had collectively put 23 military-linked companies on their ESG indexes, greenlighting them for inclusion in ESG-labeled funds, including funds managed by BlackRock, Deutsche Bank, Northern Trust, State Street and Vanguard. In total, we found that ESG indexes managed by MSCI, FTSE Russell and S&P Dow Jones Indices had directed $13.7 billion in equity investments to the 23 companies doing business with the military. Companies benefiting from this so-called “responsible investment” include weapons dealers arming the regime, tech firms serving the military-controlled national police force, and others that direct profits and resources to the military, allowing it to violently crush dissent and maintain its grip on power.

The complaints outline how each of the three firms has failed to uphold its human rights due diligence responsibilities and failed to use the considerable leverage it has over companies listed on its ESG indexes to address serious human rights risks and impacts stemming from those companies’ ties to the Myanmar military.

Inclusive Development International began engaging with MSCI, FTSE Russell and S&P Dow Jones Indices about their role directing ESG-labeled investment to Myanmar military-linked companies years before filing complaints against them. When we first published research, as part of our Myanmar ESG Files report, showing that they were including problematic companies in their indexes, we reached out to all three index providers to share our findings and discuss the steps they could take to fulfill their responsibilities under the UN Guiding Principles on Human Rights and the OECD Guidelines. Unfortunately, none of the three firms has given any indication since then that it is taking steps to fulfill those responsibilities.

Inclusive Development International first published research on ESG-labeled investment going to companies linked to human rights abuses in 2022. The Myanmar ESG Files database provided detailed information on hundreds of ESG-labeled funds we had found were invested in companies with ties to Myanmar’s military—including the specific companies they were invested in, those companies’ links to the military, the total value of each fund’s holdings in those companies, the asset managers overseeing the funds and the ESG index providers and rating and research firms those asset managers relied on. The accompanying Myanmar ESG Files report exposed the systemic issues within the ESG investing industry that allowed this to happen. The report included a specific focus on the role of ESG index creators and called on them to exclude any company from their ESG indexes if it refused to stop facilitating human rights abuses in Myanmar.

Read the Myanmar ESG Files report.

We compiled detailed information on hundreds of ESG-labeled funds.

The rising demand for responsible investment options holds enormous promise as a driver of better corporate conduct. But the ESG investing industry that is servicing that demand is fundamentally flawed. As a result, it rewards bad corporate conduct and undermines accountability to international business and human rights standards.

The industry needs to be regulated and fundamentally reformed to end ESG Washing and return it to the original values-based intent of the socially responsible investing movement that it captured.

We are calling on policy makers to institute these seven reforms to make responsible investment mean what it says and to realize its promise of building a better world:

The International Sustainability Standards Board, announced at the COP 26 climate summit, is developing “a comprehensive global baseline of high-quality sustainability disclosure standards to meet investors’ information needs.” This framework should be based on the principle of double materiality, which pays equal heed to the risks and impacts of corporate activities on people and the planet as it does to how ESG issues affect the company’s value. Corporate reporting on human rights, and the external assessments conducted by ratings firms, must be divorced from financial considerations and aligned with the International Bill of Human Rights and the expectations of businesses under the UN Guiding Principles.

Testimony from rights-holders, including workers and communities affected by a company’s operations should hold more weight than a company’s own reporting, which is highly incentivized to portray an air-brushed account of its negative impact. This can be accomplished in part through an auditing and assurance system that prioritizes the perspectives of rights-holders.

The social auditing industry, which is itself highly flawed, must be regulated to ensure that it is staffed by qualified specialists whose independence and impartiality are not compromised. Regulation must include legal consequences for ESG auditors who do not exercise due care in certifying the veracity of company disclosures.

Regulators should require ratings firms to break down ESG scores into separate and distinct categories of environmental, social and governance issues.

All companies should be assessed against the same global standards of responsible business conduct, rather than graded on a curve against industry peers, as is the current practice.

That junk rating should stand until the harm has been remediated, regardless of any grand policy pronouncements that the company makes.

When there is credible evidence that a company is implicated in serious violations, index providers should in collaboration with asset managers use their leverage to demand remedial action and remove companies that fail to repair the harms.

ESG indices linked to Myanmar junta — FS Sustainability — March 7, 2024

ESG indices under fire over Myanmar — Financial Times — February 17, 2024

Myanmar Energy Ties Are Flying Under the ESG Radar — Bloomberg — December 21, 2022

Call for US Greenwashing Rules to Extend to Human Rights — ESG Investor — August 25, 2022

The limits of responsible investing — Capital Aberto — March 13, 2022

Happy birthday to Europe’s sustainable finance directive — Financial Times — March 11, 2022

ESG Funds Scolded for Investing in Myanmar Arms Suppliers — Bloomberg — March 9, 2022

Hey, you seem interested in our work. Why not sign up to our mailing list for occasional updates, alerts and actions?

You can close this popup by clicking the black area or close button.

You can close this popup by clicking the black area or close button.